In Beer-Sheva there is a bridge that connects between Ben-Gurion University and the Gav-Yam Hi-tech park. A big beautiful bridge that not only makes it practical to connect between the two (and with the train station) but clearly symbolizes that talent, ideas, and initiatives can be very close to realize and easily transferable with the right mindset.

I spent most of my career with one primary goal, if I’m creating something then I’d like it to be found useful and to be disseminated widely. I’d really like people to use it. I find this ambition to be the pinnacle of an applied researcher, an industrialist or an entrepreneur. While the day-to-day “worries” for those are quite different, I find many similarities, way more than one would imagine between the seemingly distant titles, and I’d like to share a few of these observations: Managing taskforces, handling budgets, meeting deadlines and goals, and the holy grail – Grants vs. Investments.

Academia and Industry: Two peas in a pod

It may seem a surprise, but academic life runs in cycles. For the average research, an annual cycle where goals are planned, often summarized for publications. I’m used to running, for over 20 years, in quarterly cycles at which we execute fabrication, tapeouts, write publications and/or patents. I enjoy the stress a deadline brings, aligning everyone and weeding out distractions. The only distinguishable luxury an academic has over his industrial counterpart is that delays are more manageable, this is primarily because the risks taken in research are typically higher and the implications are more contained. So, compromising time-to-market (to publish in that case) in a few more weeks or even longer to achieve the desired results is often done. The competition there is fierce as well, don’t think otherwise. Academics fights on first-to-publish, especially on hot-topics are relentless.

Execution is a huge deal. In the industry we have an abundance of talent to choose from, and we tailor the best person, and even teams to carry out a task, academic research mostly run by novices. At least for this article, I’d set aside the entire HR details in both domains. This can and does fill in books of management, counseling and coaching.One major key of success that I’ll stress here is on the importance of health, respectful and constructive communication. This is an absolute must-have for a successful outcome, because we are all human-in-the-loop. For many years I ran research groups of anywhere between 10 to 30 Masters and PhD students, and additional 10-20 undergrads. The main factor is that students can’t be “promoted” and stay to work with you – they graduate. So you’re always recruiting, always training juniors. The trick is to create momentum, a hierarchical pipeline where you can spend more of your time and efforts with the veteran students as they bring up the new generation up to speed. Sounds similar isn’t it?

The world’s fuel is money!. As a method of appreciation, but also plain and simple as an enabler to first facilitate then accomplish results. A key component in academic life is budget handling. I have been running, on average, between 6 to 10 research programs in parallel, each has its own budget. Each comes with unique restrictions. A key component for a successful program is to properly allocate resources. In this way, you can allocate portions of the budget to training, creating that very desired momentum.

When you have money, you need to manage it properly. Ok makes sense. But how would you get this funding? Where and to whom do you pitch your ideas? Investors fund businesses. Grants fund research. Grants may come from governmental entities, but in the many cases of applied researches funding comes out of the industry. I’ve been collaborating with the industry, both in Israel and abroad in creation of new lines of products, developing new divisions, setting up incubation and acceleration programs and licensing IP. This may come as a surprise, but winning research grants is the most important metrics of today’s faculty. Academics qualities are measured by publications and with much heavier weight – funding, since without it you can’t fuel your research. Rings a bell? Moreover, this may come as a surprise, but more than half of an academic salary actually comes from those budgets. The university grants a faculty basic facilities – an empty space for lab and office (and if you’re lucky, some startup/seed money upon acceptance) from then on – you’re on your own.

The typical metrics for a VC seed investment of a startup are that there is a timely idea which addresses a wide and attainable market, and perhaps the most important – that the team of founders are adequate to execute and convert a set of slides into a real company. What are the metrics for winning a research grant? Lo and behold – are the same! There is a groundbreaking idea, useful to mankind (ok, big words) and that the proposing researcher has the background, skills and infrastructure to execute the program. In a very similar way many startups are not getting funded because the team isn’t “fundable” enough, many more research grants are rejected because the reviewers weren’t convinced that the researcher is up for the challenge.

Now from that perspective from both ends of the bridge, I can testify that successful researchers are basically entrepreneurs and vice versa. The same skill set applied, but at times to achieve different goals. Both operate under uncertainty, manage multidisciplinary teams, and must produce measurable outcomes within a strict timeline. The distinction lies in scale but more in audience.

Running a research lab taught me how to orchestrate complexity: people, technology, and resources, all while pushing the limits of what’s possible. In retrospect, I always have been an entrepreneur; I just happened to be working on the other side of the bridge.

Power-in-Motion: Turning Research into Reality

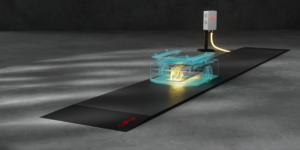

CaPow was born in my research lab. The marvel of freedom of positioning for energy transfer wouldn’t have been possible any other way. So many building blocks had to be literally invented, or to the very least heavily modified to the power domain. So, only a combination of maturation of technology as separate functions with exquisite talent that has grown within the evolution of those foundations has created the perfect combination to take it to the next level of a full fledged product and scale. Together with my two PhD graduates, now my bro-founders at CaPow, Dr. Eli Abramov and Dr. Alon Cervera, we took the capacitive power transfer technology and created Genesis.

Genesis is a market-unique solution that provides power in-motion, en-route to autonomous robotics operating in industrial manufacturing and logistics sites. It eliminates the need for charging stations and idle time. Fleets operate continuously, achieving 100% uptime and up to 35% lower total cost-of-ownership. Our energy-management software, GEMS, monitors and optimizes power flow in real time, turning energy from a hidden constraint into a visible performance asset.

The bigger picture advantage, beyond improving operational efficiency, savings in CAPEX and OPEX, is that CaPow allows operators to disengage from any energy constraints or restrictions and focus on optimizing their process. Achieving optimal performance out of the robotic fleets without considering the routes the robots would deviate to because they are running low on battery or even on where to place a charger or how much would it cost to modify the infrastructure to have a charger – All of those worries are a thing of the past, all gone. Same goes to OEMs

who design and manufacture robots. All worries of how big the battery should be, or how to design the robot to accommodate this bulk are no longer a constraint.

CaPow has become a global company with teams in Israel, Europe, and the United States. We expand everyday and make a real impact on automation efficiency, while continuously evolving our offering and expanding the product portfolio through systematic and efficient R&D. The market credibility of Genesis is being strengthened everyday, with leading manufacturers such as Hyundai Glovis, and integrators like ACS, JLC Robotics, as well as tier-1 manufacturing companies producers across North America.

Header Photo: HyundaiGlovis

Credit: CaPow