An international team of scientists has tailored special X-ray glasses to concentrate the beam of an X-ray laser stronger than ever before. The individually produced corrective lens eliminates the inevitable defects of an X-ray optics stack almost completely and concentrates three quarters of the X-ray beam to a spot with 250 nanometres (millionths of a millimetre) diameter, closely approaching the theoretical limit. The concentrated X-ray beam can not only improve the quality of certain measurements, but also opens up entirely new research avenues, as the team surrounding DESY lead scientist Christian Schroer writes in the journal Nature Communications.

Although X-rays obey the same optical laws as visible light, they are difficult to focus or deflect: “Only a few materials are available for making suitable X-ray lenses and mirrors,” explains co-author Andreas Schropp from DESY. “Also, since the wavelength of X-rays is very much smaller than that of visible light, manufacturing X-ray lenses of this type calls for a far higher degree of precision than is required in the realm of optical wavelengths—even the slightest defect in the shape of the lens can have a detrimental effect.”

The production of suitable lenses and mirrors has already reached a very high level of precision, but the standard lenses, made of the element beryllium, are usually slightly too strongly curved near the centre, as Schropp notes. “Beryllium lenses are compression-moulded using precision dies. Shape errors of the order of a few hundred nanometres are practically inevitable in the process.” This results in more light scattered out of the focus than unavoidable due to the laws of physics. What’s more, this light is distributed quite evenly over a rather large area.

Such defects are irrelevant in many applications. “However, if you want to heat up small samples using the X-ray laser, you want the radiation to be focussed on an area as small as possible,” says Schropp. “The same is true in certain imaging techniques, where you want to obtain an image of tiny samples with as much details as possible.”

In order to optimise the focussing, the scientists first meticulously measured the defects in their portable beryllium X-ray lens stack. They then used these data to machine a customised corrective lens out of quartz glass, using a precision laser at the University of Jena. The scientists then tested the effect of these glasses using the LCLS X-ray laser at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in the U.S.

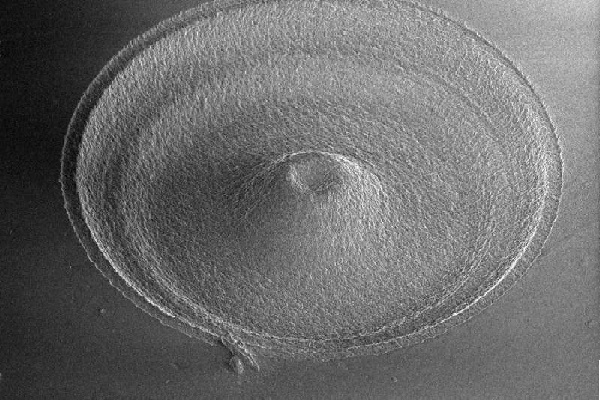

“Without the corrective glasses, our lens focused about 75 per cent of the X-ray light onto an area with a diameter of about 1600 nanometres. That is about ten times as large as theoretically achievable,” reports principal author Frank Seiboth from the Technical University of Dresden, who now works at DESY. “When the glasses were used, 75 per cent of the X-rays could be focused into an area of about 250 nanometres in diameter, bringing it close to the theoretical optimum.” With the corrective lens, about three times as much X-ray light was focused into the central speckle than without it. In contrast, the full width at half maximum (FWHM), the generic scientific measure of focus sharpness in optics, did not change much and remained at about 150 nanometres, with or without the glasses